Report 2017

Made in Cornwall

by Liam Jolly, a participant

As I was nearing arrival at the Cornwall Workshop, I remembered something David Bowie said: ‘Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.’

For sure I was heading into deeper water: I hadn’t been involved in anything like this before. Of course Bowie was right, but I wondered why I found myself so nervous.

Perhaps it was something to do with meeting a large number of individuals, none of whom I knew, for the first time, and wanting to make a good impression. Perhaps it was the thought of living with them for a whole week; what if we didn’t get on? Perhaps it was simply the fear of the unknown.

Friday 6 October

Despite my best efforts to dally on the way, I was the second to arrive. Damn. As more joined I got the sense that others too were anxious about finding themselves out of their depth. But after several cups of tea and lots of handshakes we were off in the minibus for our first excursion: a talk by geologist Dr Ruth Siddall, about the use of Cornish and Devonian stone in London’s infrastructure, with supper afterwards at CAST in Helston.

The talk was extremely interesting and I wish I had made notes. I was staggered to discover that many of the capital’s iconic Portland stone buildings are set on granite plinths. There was something quite poetic about the way in which this talk also laid foundations, both literal and metaphoric, for our week ahead, while also immediately serving as an icebreaker for the supper that followed.

Saturday 7 October

The day began with breakfast in the main barn. Kestle Barton is a beautiful place to be. Although it’s only 40 minutes’ drive from my house, I am not that familiar with this part of Cornwall and I felt I could be far away. It’s peaceful and relaxing, with stunning accommodation.

After breakfast, we decamped to a studio where each of us would give a 10-minute presentation on our work. I hadn’t done one of these since art school, and nerves kicked in again, not least because I’d only just met my audience.

Nearly three hours in, we realised we were in for a long haul; we’d only heard from three people. As I was one of the last to speak, I resigned myself to the fact that it was going to be a disaster; the standard so far had been really high. Just before my slot, we heard from Gemma Anderson and Gina Buenfield who both presented exceptional talks. Gina had recently come back from the Amazon where she’d been on a sabbatical from her day job as Exhibitions Curator at Camden Art Centre and had been living with a medicine man as part of her ongoing research. Gemma talked about her PhD, located at the intersection of art and science and looking at animal, vegetable and mineral morphologies, as well as the ideas that make up her recently published book Drawing as a way of knowing in Art and Science.

Working across installation, video, performance, painting and public intervention, my practice is process-led and playful. In absorbing the depth and breadth of these presentations, I began to question my judgement in deciding to open the talk with a fixed viewpoint film that features nothing more than racing greyhounds passing at random intervals. But it was too late. It was now my turn.

I described how my works consider the relationship between language and visual experience, and more specifically between fiction and reality, and talked about ongoing projects involving drum patterns, live buskers, football players and fake gig reviews in the local paper. There was lots of positive discussion and feedback around my questioning of how something comes to be regarded as an artwork, or not.

40 minutes later and a whole 24 hours into the Cornwall Workshop the pressure lifted. My talk was over. It had gone well. Collectively we had made it, we had all shared and exchanged our work. As we broke for dinner the change in atmosphere was palpable and everyone was in a much chattier mood.

During dinner, I discovered that others had been similarly anxious: a real eye opener. Perhaps whatever your level of achievement such feelings never really leave. And so, Bowie’s advice is good for all artists, because we’re always pushing ourselves out of our comfort zones in the search for something new and better. Anyway, I was now more confident about my place on the workshop. I was really looking forward to the rest of the week.

Sunday 8 October

The next day we had some hours in the morning to ourselves. Some brave souls went swimming, others for a walk. Looking forward to the afternoon’s expedition, I caught up with emails.

Our walk was led by artist Anthony Bryant and mining specialist Stephen Polglase. They took us to the Great Work Mine, near Helston, which at one point employed up to 3,000 people, and then on to Tregonning Hill with its 569ft peak. Looking east, from the point at which William Cookworthy first discovered China Clay in 1746, Anthony pointed to another mine – Wheal Vor. I realised that this view would have been very different 200 years ago: far more industrial. Today, it’s more often the other way around, with nature giving way to urban sprawl and technological advance.

Anthony, and Stephen whose family had worked these mines for many centuries, spoke passionately about the landscape, which both of them had known since childhood.

On our descent, we saw a clay pit that had served the Tregonning Hill Brickworks – though all that remains of the latter’s infrastructure is a magnificent Grade II listed circular Kiln.

On our way back to Kestle Barton, Teresa suggested a stop-off at St Breaca Church in Breague. With only the torch light from our phones for illumination, we viewed the amazing frescoes on the north wall. Imagine the CCTV footage of the scene.

Monday 9 October

Christina Mackie, the lead artist for this edition of the Cornwall Workshop, had asked us to bring along something as a way of starting to share ideas and interests. Having just moved studio, I’d recently unearthed boxes of stuff that I’d kept from over the years. But what to take?

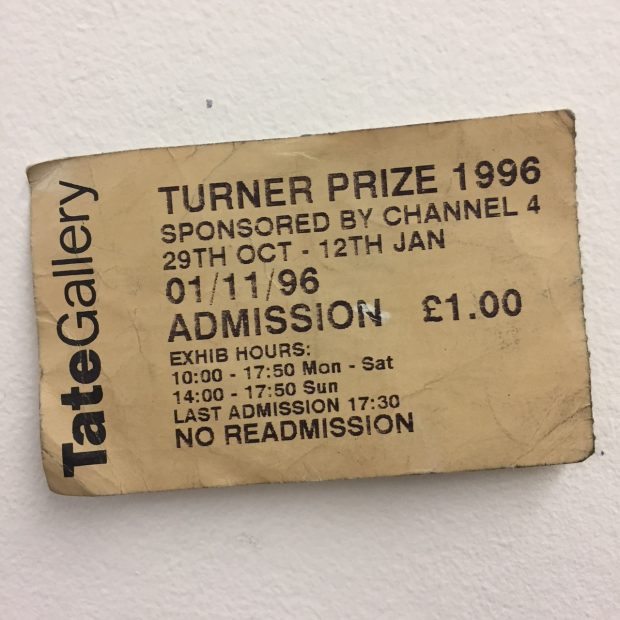

I settled on a ticket for the 1996 Turner Prize exhibition, which represented a pivotal moment for me in terms of understanding art and its possibilities. Things that other people brought included a root, a Dave Eggers short story, a photograph of Robert Chalmers Bisson’s text-covered house in Jersey, a collection of black pigments, and a piece of contemporary classical music by Eberhard Shoener. We even had the Helston Furry Dance.

Not only did these things serve to introduce individuals’ history and their thinking, but they also enabled us to see connections and associations within the group and across our practices, producing a web of collective thought that brought us still closer.

Tuesday 10 October

An early wake-up call might be the last thing you’d want after a night of impromptu partying (we were celebrating Gemma’s birthday), but today it was welcome. A boat was taking us, with artist Abigail Reynolds, up the Helford to visit Tremayne Quay.

On this crisp morning, we were welcomed with the smell of sausages and bacon being cooked on an open fire. While some of us chatted about the previous night’s antics and, of course, how we were finding the workshop so far, others made the most of this waterside location to pursue their daily ritual; our conversation punctuated by the sound of bodies plunging into cold water.

Abigail is currently working on a project for Tremayne Quay that will be part of the 2018 Groundwork programme and after breakfast we talked about the ideas she’s developing, based on the particularities of the site and involving a performance by the St Keverne Band.

The quay was built in 1847 to welcome Queen Victoria, with red-carpet laid from the waterside up towards the village of Saint Martin. But the Queen never came. So the carpet was cut up and distributed among local residents and for many years it could be found in their homes: a wonderful image.

Later that day, after a walk through the woods, we made an impromptu visit to local architect Matt Robinson’s extraordinary garden and to the round field – an Iron Age settlement – at Caervallack. And then, back at Kestle Barton, we were joined by artist Naomi Frears, who told us about a project she’s working on in collaboration with electronic DJ and producer, Luke Vibert.

Like Abigail’s, Naomi’s project is still very much a work in progress, with many moveable parts. We discussed what it might become and offered some suggestions. Here was another good example of the value of a network and of the way in which the energy of a group can move things on very quickly.

Wednesday 11 October

Chris Fite-Wassilak had joined us the previous evening and plunged immediately into the group spirit. Today he led us in a writing workshop. Again, our ‘thing’ was the starting point, as we were asked to describe it with two verbs and adjectives. The room fell silent, until Ben dared to ask what a verb and an adjective actually were, which resulted in collective relief. And then a discussion of the failings of the educational system.

After staring at a blank page for some time, my words began to flow, getting more adventurous. I’ve since found this to be a great mechanism to get started in the studio: using language as foundation on which to build, just as those London buildings used granite.

Later that day, with a new-found delight in looking at the most ordinary of details and trying to find words to describe them, we headed off to Christina’s guest lecture at Falmouth School of Art – our first chance to hear her talk about her work.

She said she likes to think about ‘how small we are on this rock we’re on’; clearly she considers perception, scale and worth. She uses natural and man-made materials – often valueless – to make art that doesn’t look like art, which is also purposefully in a state of flux; all ways in which the form expresses her ideas. Moreover, the inclusion of multiple objects within her installations creates a web of readings and associations, enabling a space in which to explore new ideas. The works she presented offered starting points for trains of thought and feeling, not full stops – just as our objects had for us.

It soon became clear that Christina’s approach to her practice, with a focus on process, informed her role as workshop leader: letting things unfold. With us, this meant that the direction, dialogue and narrative emerged as we went along, while aiming to respond to the question of how to start a piece of work, or at least to start again.

We’ve got it made in Cornwall

Throughout the week we were joined by a range of guests, some programmed, some not, but all contributing in one way or another to the ideas and discussions that emerged as the workshop progressed.

Andrew Lanyon was the first, showing some of his films – part of a prolific practice that also includes song, painting and writing. His films were fantastic, quite absurd and sometimes very funny. The energy in his work is inspiring, as was his claim that ‘there’s nothing with more integrity than a mistake’.

Then there was the memorable appearance of the Redruth rappers Hedluv + Passman. Over lunch one day we’d mentioned our admiration for this duo, which inspired putting in a call to try and arrange our own private performance – they were waiting for us when we returned from our Falmouth trip. A swift late supper, the arrival of some extra guests, and we were treated to a show by one of the most entertaining of Cornish acts.

In the course of the week, we had claimed certain things for the group. The first came from Stephen Polglase, the mining specialist, whose phrase ‘where it is, there it is’ – used in the search for a vein of tin – felt wonderfully relevant to Christina’s question of how to start a new piece of work. Then there was the ‘sofa-tunnel’ game, which emerged at the end of our mammoth day of presentations. Led by Gemma Anderson, participants were timed as they crawled through the cushioned structure – and disqualified if it was damaged. It got very competitive! But if there was a soundtrack for CW17, it was Hedluv + Passman’s rousing anthem ‘Made in Cornwall’.

The final day – Thursday 12 October:

The mood in camp on the final morning was quieter. It was a beautiful day, and we sat outside chatting and completing tasks from the previous day’s workshop, later taking the opportunity to meditate. Ruth Siddall’s talk on that first evening felt like a lifetime ago. I was trying to process it all. I now realised how isolated I had felt before the workshop: although always trying to progress, I was stuck in a rut.

The aims of the Cornwall Workshop are to provide a critical space for discussion and debate, while encouraging ongoing working relationships between participants. In 2017 it certainly achieved all of these. Instantly I had colleagues; life-long friendships had been formed, networks expanded. There were plans for follow-up projects, crits, and possibly an exhibition. And the level of critically engaged conversation throughout the week had left me with a confidence in what I was doing, and knowing that the path I was on was the right one. I was not in a rut.

An impromptu afternoon spent on Carn Brea concluded the workshop. The hill that overlooks Redruth is topped by spectacular granite tors, with Neolithic ramparts and a Victorian monument referring to the area’s mining past. This was a perfect bookend for the week. For most of my life, I’ve lived at the bottom of Carn Brea and maybe I’ve taken this backdrop for granted. But it now has new significance as a daily reminder of the workshop with its invaluable experiences and outcomes.

As I sat on one of the rocks taking in this vast yet familiar landscape in the company of this wonderful group of individuals who, a week ago, I didn’t know, I felt connected in a way I’m not sure I’ve experienced before. Finally, I was part of a network where I could see potential to develop professionally. And all within a region that I had once thought had very little to offer.

Whilst all nestled in a rock formation known as the ‘cup and saucer’, we found ourselves singing our adopted Hedluv & Passman anthem. It couldn’t have been a more fitting way to end what had been a truly wonderful week.

The Cornish Archeology Journal, No 47, 2008

Images: courtesy Liam Jolly and Teresa Gleadowe.

Text © Liam Jolly and CAST (Cornubian Arts & Science Trust), 2018. Liam Jolly lives and works in Redruth, Cornwall: liamjolly.com