Report 2019

Instances of Exceptional Resonance

by Mollie Goldstrom, participant

Arrivals/An Eerie Calm

“The eerie also entails a disengagement from our current attachments. But, with the eerie, this disengagement does not usually have the quality of shock that is typically a feature of the weird. The serenity that is often associated with the eerie—think of the phrase eerie calm— has to do with detachment from the urgencies of the everyday.”

Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie

On a rainy late afternoon at Kestle Barton, the trees bleed into a low, saturated sky. I am afflicted with the particular condition of arriving first, which affords the observational advantage of noting each of my cohort as they appear one by one, while imagining I’m the not-quite-omniscient narrator of a parlour mystery. After all, the basis for our assembling here seems an ideal premise for a detective story: fourteen individuals – artists, educators, curators organisers – many of whom are meeting for the first time, gather at an ancient and remote Cornish farmstead to await the arrival of their mysterious hosts, who have invited them here for something called ‘The Cornwall Workshop’.

I wait in the communal space of the central barn conversion, airy and light-filled in spite of the overcast weather. These broad-beamed pine tables will be the focal point of so many discussions and shared meals over the course of the week, their present bareness foreshadowing the bustling conviviality soon to come. Beyond the big glass doors that lead to the garden, a tree laden with green-gold apples sways beckoningly as evening starts to draw in.

With each new arrival tea is prepared, steaming cups multiplying on the recently empty kitchen island as introductions are made, made again. As our numbers increase the space swells with our voices, a single conversation fracturing into polyphony. Other sounds multiply, the intermittent percussion of footsteps as every individual seeks to acquaint themselves with novel surroundings: the juddering staccato of suitcases being wheeled across stone and uneven turf, the squeak of a door opened and shut repeatedly, the whoosh of air accompanying each body passing over the threshold. At some point tea receptacles are shunted aside in favour of wine glasses. As we sit down to eat I glance around the table at our assembly. Some of us have come directly from Extinction Rebellion actions in London, some have driven a terrifically long distance, or taken a train, others, including myself, have travelled just a few miles. Andy Holden, the artist helming this workshop, arrives from Inverness, where he has just finished installing the latest iteration of ‘Natural Selection’, an ornithological panoply made in collaboration with his father, Peter Holden, who is also present.

Can a ‘thin place’ be temporal? For we are fresh to this place, each of us still a little between worlds, still inhabiting our external concerns, the air of our various points of origin clinging to us like caul. How easily will we disengage from our worries, routines, and attachments? Wine is poured; we raise our glasses in a toast.

Swee! Swee! Swee! Swee! Swee!

On Saturday morning Peter Holden leads us on a walk around the Helford Estuary, beginning at St Anthony in Meneage, to the headland of Dennis Head. A leading ornithologist with 45 years of work with the RSPB under his belt, he has joined us for the weekend at Andy’s behest. We gather around him to face the fourteenth-century church tower to follow the flightpath of blackbirds. Their burbling trill is interwoven with human chatter in the distance— we are not the only walkers on this particular morning. Peter is primarily interested in understanding what exactly they are doing at the moment and why, something I have never specifically considered when birds in flight cross into my line of vision: what exactly are they doing?

The tide is fairly low, exposing an expanse of stepping stones overgrown with tangled dull green wrack. The prospect of using them to cross these shallows to the opposite side of Gillan creek seems plausible— a few of us are taking tentative steps forward, trying to ascertain whether the shifting seaweed will be destabilising enough to send one tumbling. Not trusting the rocks, I follow the example of a few others and remove my boots and socks to wade through the bracing water.

Following a lively dinner at CAST Café that evening, Holden father and son deliver their dual performance lecture on birdsong, reprising a performance previously delivered at Tate Britain, in one of CAST’s second floor studios. Our small group is joined by other Cornwall-based artists and interested members of the public. Standing before an illuminated projector screen, their interwoven narrative is riveting, outlining the complex relational mesh existing between humans and birds, an expansive exchange encompassing sheet music notation and early field recording as attempts to understand and transcribe birdsong, and, hauntingly, nightingales responding in duet to the alfresco cello playing of Beatrice Harrison, broadcast live by the BBC until 1942, when birds and instruments were joined by the identifiable drone of bombers flying overhead.

Aerodrome

The waning afternoon is sensuous, the sunlight revelatory when we emerge outdoors following a long and intensive second round of presentations of our widely varied creative practices. Andy has added a novel twist to an otherwise familiar exercise, asking that we primarily illustrate our talks with our social media accounts. This reveals surprising and nuanced glimpses of how each of us moves through the world in addition to what we produce. The anticipatory tension that accompanies having to speak in front of an audience, no matter how intimate, has now dissipated, replaced by a greater collective ease and camaraderie.

I am uncertain as to where we are being conveyed when we board the van. My familiarity with the greater Lizard Peninsula is like a puzzle missing most of its pieces. Small villages pass by as we pursue the fleeting sun towards our final denouement. Once on foot, rather than follow the coast path towards the cliffs, the crooked snake of our group winds past a ‘no trespassing’ sign and shortly the mud and coastal grass underfoot gives way to the cracked tarmac of Predannack Airfield. Time has been sucked from this place, a flat expanse dotted with the carapaces of decommissioned military planes of indeterminate vintage. We may well have passed through some temporal fissure to be deposited centuries into the future. We disperse, drawn mesmerically towards the grounded planes. I brace myself for potential structural collapse as I climb the chassis of a bomber jet to join a few intrepid others, but it merely lists benignly, encouragingly even, to accept the additional weight. Any immediate threat of danger dispelled, we run from wingtip to wingtip, causing the plane to seesaw. As the wings dip from side to side, Andy records the atmospheric, metallic creak and sigh of the reanimated plane. The paved ground feels reassuringly solid upon dismounting, as we continue our exploration.

Approaching a row of dummy aircrafts in shallow pools of rippling rainwater meant for fire extinguishing practice, the concurrent Simon Faithfull exhibition at The Exchange in Penzance comes to mind. One video in particular features a silver-suited personage traversing the hulking chassis of a jet plane as it erupts into flame, the sequence both terrifying and dreamlike, the calm manoeuvrings of the solitary figure around the flickering aircraft entrancing in their rote repetitions. We line up in front of a similar carapace for a group photo before the sun dips further, making our way back to the van in near darkness.

Interlude: Interspecies Table Tennis

Landscape Poems

October at Kestle Barton is a time of apples; apples on the floor and glowing in the trees. For the entire duration of the Cornwall Workshop, juice is being made from the fruits of KB’s heirloom orchard, apples and industry forming a sensory backdrop to the week. Windfalls have tumbled to the ground in a richly scented, decaying carpet. We pluck the low-hanging fruit to taste, make field recordings of the cider press in action. To tread upon fallen apples in dappled sunlight and feel the gentle give and crunch underfoot elicits a frisson of pleasure.

We will consider many definitions of landscape from varying vantages over the course of the week. We watch By Our Selves, a poetically surreal twenty-first-century recreation of poet John Clare’s walk from an asylum in Epping Forest to his former home over 80 miles away in Northborough. Layers of change and loss are threaded through this film’s topography, from the early-nineteenth-century acts of enclosure dividing the countryside, to the banalities of the modern roadways that Toby Jones staggers along in his cinematic portrayal of Clare. Andy makes an impromptu video call to its director, Andrew Kötting, summoning us when contact is made. We have caught him just as he was about to leave his office. Suddenly faced with his projected presence, we defer to Andy to be primary interlocutor. After entreating Andy to get a haircut, Andrew discusses the making of this and others of his films, several of which revolve around psychogeographic pilgrimages.

We take a spontaneous nocturnal walk through the woods into Helford, relying on our senses of hearing and touch to spatially orient ourselves and communicate to one another about potential obstacles along our path.

For me, the experience of listening to one another read a favourite landscape poem gathered around a patio table in the garden on a sunny afternoon is one of the most profoundly peaceful and generous moments of the workshop.

Two Circles Near Redruth

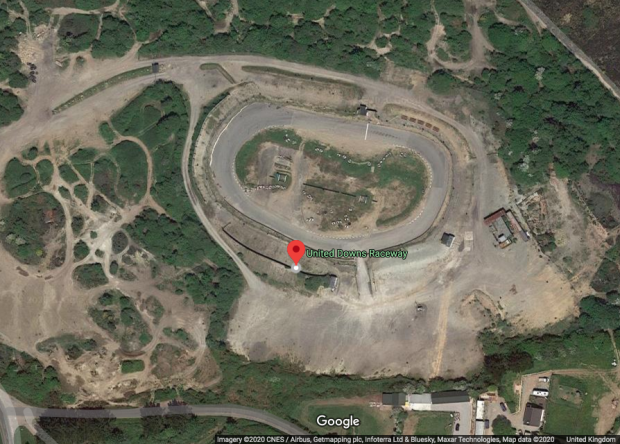

Teresa proposes a visit to a region of former mine workings outside of Redruth. Walking on a section of the bike trail that runs between the north and south coast, we pass the truncated stone ziggurat of the ruined Bissoe Arsenic Works. At Gwennap Pit, an idiosyncratic outdoor amphitheatre and relic of both the Methodist movement and mining industry, we attempt to fill the tiered concavity with our bodies, voices and movements, walking annular rings around one another, exchanging high fives when our paths cross. Our next stop is United Downs Raceway, where we are introduced to Binrat and Niddy, a local artist duo who have returned to the site of the Bangers and Mashup festival that they organised this past July to give us a tour. Peering at the photos of the pair’s fantastical sculptures and structures welded from an array of repurposed metal parts, I try to imagine this racetrack filled with people, art, food and music, but on this grey day, it is almost as difficult as it is to picture 50 years of stock car racing taking place here, or, for that matter, John Wesley preaching to an audience of thousands assembled concentrically at Gwennap Pit in the second half of the eighteenth century. United Downs Raceway and Gwennap Pit are spaces intended for large gatherings of spectators; we have caught both at a temporally disjunctive moment of rest. Located less than a ten-minute drive apart, they feel synchronous. Even though both sites are still in use (Niddy and Binrat are in the planning stages of a second iteration of their festival for the summer of 2020), they feel haunted when we visit them, thronged with the absence of multitudes.

Poussin’s Landscape With A Man Killed By A Snake

One of the themes proposed by Andy for this workshop is ‘Kant After the Internet’; indeed, many of our discussions revolve around the reflective contemplation of the fragments of sound, image, video, text, and meme that we have chosen in advance for their particular resonance, perhaps to interrogate our choices as manifestations of external phenotype, as if we were bowerbirds selecting a pleasing spread of objects to enliven our structure of sticks. What will we understand about ourselves and each other in examining our relationships to these virtual objects? The ensuing conversations range freely over a wild assortment of subjects, not limited to toxoplasmosis, slime moulds, telekinesis, Margaret Hamilton’s Apollo mission source code, the queue of hikers waiting for their turn atop Mount Everest, and the fate of hundreds of film reels dislodged from a decommissioned swimming pool in a Yukon ghost town.

In the darkened apple-store-turned-seminar-room we creak forward in our chairs to see the projector flicker to the next of our selections, the image of a canonical painting from 1648. The painting fills the screen; even at a low resolution it is arresting in its depiction of the pre-internet movement of information, a ripple of bad news traceable from the prone, snake-draped corpse in the foreground of a bucolic landscape to a messenger running in terror, to a woman in the middle distance looking up from her washing, sensing that something is amiss. In the background three figures in a boat are blissfully unaware of any tragedy or danger nearby.

Over the course of the week a nascent web of connection between everything that we read, watch, listen to and experience tantalises as it comes in and out of focus, uniting the obsessions of nineteenth-century collectors with the twenty-first-century delight of a viral cat meme; Daisy Hildyard’s Second Body and Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects; OoL – the Origin of Life – and Oology – the branch of ornithology devoted to the study of bird’s eggs.

De Natura Sonorum

The arrival of Mira Calix late in the week injects a new energy into our midst. She is here to impart to us knowledge concerning the nature of sound. On her first evening, in an intimate gathering at CAST, she introduces her work to our group and a lucky few others. The room is hushed as she presents documentation of Nunu, her musical composition evolved into an expansive iteration involving the collaboration of the London Sinfonietta and an assortment of live insects, whose every rustle, click, and chirp is amplified within the space of a concert hall. In a true derangement of scale, live streamed footage of the insects dwarfs their human counterparts on large screens. Mira also presents a range of her other compositions intended to be performed or broadcast from radically different spaces, which include a monolithic gneiss sculpture in Redbridge, a commuter-bus-turned-mobile-museum in Nanjing, and the Tower of London. She invites us to contemplate the particulars of how sound is recorded and delivered back to an audience.

These considerations play an important role in her daylong workshop, which starts with a lecture on the history of field recording, its applications within ethnomusicology, acoustic ecology, reportage and composition. Mira presents a survey of pioneering sound artists and early proponents of musique concrète, playing extracts from works by Bernard Parmegiani and Luc Ferrari, and Bernie Krause’s rhythmic recordings of amplified trees – syntheses of field recording and acoustic instrumentation.

We watch dynamic footage of water drumming by the women of the Banks Islands of Vanuatu, and contemplate what Mira describes as ‘harnessing the properties of sound to make sound’.

A Few Metres of Conduit

After an initial exercise in making sample recordings using our phones, we divide into small groups, with the goal of gathering auditory fragments of landscape to incorporate into collaborative compositions – an undertaking that absorbs us long into the night. I have scant prior experience of working with sound, and Mira’s presentation of the many considerations of both capturing and conveying it is eye-opening, necessitating spatial thinking, consideration of one’s distance and perspective relative to the modulations being recorded.

My fellow collaborators and I set off down a wooded path adjacent to Kestle Barton just as a light rain starts to fall. Unsure of what we are after, we pause before a few metres of conduit which cuts through a patch of fern-plush ground adjacent to the trail, effectively an instrument embedded within the landscape itself. We spend awhile testing its acoustic properties, speaking, singing, whistling through it, stomping and skipping over it. We take turns recording from different vantage points.

We return indoors, to polish what we have collected in the glow of a laptop screen. Mira, making rounds between groups, offers advice and assistance. Both Rachael and Emily have utilised sound editing software for their own work previously, so they take the technical helm as we pool our more esoteric annotations and ideas. I, a relative Luddite, propose abstract annotations and ideas, while they take the technical helm. We are already excited by the possibilities of our initial field recordings and the process of assembling them into a piece of music progresses naturally; we wrap up our composition with a degree of confidence that surprises us – the intuitive feeling of having created something worthwhile in a short space of time.

The Aesthetics Game

On the final night of the workshop we corner Andy about the glaring omission of an activity proposed on the outlined schedule. What is the ‘Aesthetics Game’, why haven’t we played it yet, and why don’t we play it now? Everyone is a bit giddy from nearly a whole week spent reading, discussing, sharing, watching and walking, and then from the day’s full-tilt exercise in field recording and musical composition with Mira.

The accoutrements of the Aesthetics Game are whatever happens to be within reach. One player places an object in the centre of the table, the next positions another object in relation to it, and so on. The game encapsulates creation, destruction, harmony, entropy. Each turn has the strategic weight of a chess play as the participant makes a move in accordance with their innate sense of the agreeable, the beautiful, the sublime, and the good. After a couple of rounds of the Aesthetics Game, the table resembles a marginally less explosive reconstruction of Fischli and Weiss’s The Way Things Go, in miniature. A group effort, there is no winner as such, but very definitely an ending, when the tableau is unanimously deemed ‘finished’.

Synthesis

We are sitting together in complete darkness, for one last time. Following a blustery morning of packing and putting things in order, we depart from Kestle Barton, which has come to feel like home for the past week. Now, in CAST’s black box screening room, we are quiet as the reverberations of the place we have just left ebb and flow around us. Birdsong, the lowing of farm animals, the mechanised pulse and squelch of pulping apples, a phone conversation in the hushed enclosure of a car, footsteps on gravel, sonorities of woodland floor and trickling water, swelling and faltering in layers of sonic collage. Alongside this final listening session of our sound works, we collectively sense other coalescences, an emergent culture endemic to the workshop itself, consisting of shared frames of reference, modes of interpretation and critical thinking, and most importantly: humour. This week has imparted a new armature for self-examination from numerous distances and perspectives, in the physical and virtual worlds, locally, globally, ecologically.

And now, following a final meal shared in a light-flooded CAST project room, it is over, all too suddenly.

When I am asked to describe this Cornwall Workshop I will by necessity draw on Timothy Morton’s concept of the hyperobject, the totality of its scope and vision impossible to realise in the particular local manifestation of a single week at Kestle Barton. But its repercussive echoes of precocity and ambition will be recalled and felt for a long time to come: a well to keep drawing from to offer curiosity and sustenance in difficult times to come.

March 24, 2020

Images of Artworks:

Still from: ‘Reenactment for a Future Scenario #1: EZY1899’, Simon Faithfull, HD video, 12min, 2012. Image: courtesy the artist

Landscape With A Man Killed By A Snake, Nicolas Poussin, 1648. Image: Wikipedia Commons

The Way Things Go, excerpt, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, 1987, video embedded from Guggenheim Museum’s YouTube

Images of the Workshop: courtesy of Jane Darke, Georgia Gendall, Mollie Goldstrom and Alice Mahoney

Satellite images: Google Maps